As I continue to mine the deeply embedded treasures of YouTube, I’ve dug up another diamond in the rough, a 27 year-old documentary on unlicensed shortwave broadcasting radio. Titled “Inside Pirate Radio,” this hour-long video visits the studio of Radio Wolf International during one broadcast, interspersed with an interview with Andrew Yoder, one of the foremost authorities on shortwave pirates, and the author of several books on the topic, including Pirate Radio Stations: Tuning in to Underground Broadcasts and Pirate Radio Operations.

Credited to the Franklin Video Group of Franklin, Indiana, this low-budget DIY video is less a documentary than a slice-of-life document. What’s most fascinating is that it’s a snapshot of the scene from the pre-internet days, when communication between broadcasters and listeners was mediated through magazine columns, printed newsletters and mail correspondence.

The appeal of shortwave pirate broadcasting is that the signals travel long distances, across continents and oceans. To understand the power of this medium one has to recognize that in 1990 few people outside the military or research universities had internet access. Long distance or international communication via phone was very expensive, and via mail it was slow.

That’s why Yoder dispels the notion that pirate shortwave broadcasting is all that exciting, explaining that there’s “no immediate thrill” in hearing from your audience. Unlike a DJ in the studio of licensed station, shortwave pirates didn’t give out phone numbers for fear of leading the FCC to their doorstep.

Instead, shortwave pirates received reception reports from listeners through the mail. But this process could take weeks, because most stations got their letters via mail drops, third parties who would forward mail back-and-forth on behalf of broadcasters in order to keep their locations secret.

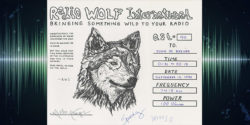

In exchange for sending a reception report, listeners could expect to receive a QSL card. It’s a postcard specifically designed by the station confirming that the listener heard an actual broadcast. Shortwave pirate listeners collect and covet these cards, and Yoder shows off his album of them in this film.

Mail drops and QSL cards still exist today, just as shortwave pirate broadcasters continue to seize the international airwaves. Message boards and social media help some broadcasters more quickly publicize their broadcasts, and some also accept email reception reports, accelerating the exchange.

Although I’ve been aware of pirate shortwave culture since the mid 1990s, watching this video I was reminded of how community and social exchange forms the backbone of the broadcasting and listening aspects of the hobby. I see parallels to cassette culture—as I wrote about a week ago—in which the exchange of home-recorded and reproduced tapes was facilitated by ads and reviews in ’zines and magazines, alongside shows on college and community radio stations. Listeners had to send away for tapes, for which they paid a small amount of money, or sent their own home recordings in trade.

As long-time DJ and musician Don Campau explained, through the exchange of letters and cassettes, “[t]ape culture also offered a way to create relationships with people, too.”

Andrew Yoder is still active as a shortwave pirate listener, documenting stations he finds at his Hobby Broadcasting Blog.